What I talk about when I talk about Japanese Literature

Anukrti Upadhyay (India)

I have visited Japan many times in different seasons for different reasons in different moods in different states of mind but I have never been not smitten by it – by its urban magic and wooded wonder; its temples and shrines and skyscrapers and eateries; silent crowds in brightly-lit metros and raucous laughter in dim clubs; hostesses dressed in fantasy costumes handing out restaurant fliers and geishas in traditional garb waiting to board a Shinkansen. I have looked at the neon-lit night of the Ginza district and star-filled sky in Hakone with equal fervor, walked along the Sumida and the Kamo with identical sense of calm motion and observed social etiquettes and bowed and smiled and looked away and stood on the right side of the escalators in Tokyo and the right side in Osaka with equal incomprehension. I have reflected upon the utter impossibility of understanding the subterranean motivations and compulsions of a culture and yet admiring its outward depictions; I have been entranced with the aesthetic which with one flower or a spray of grass, a brushstroke or hand movement seeks to convey seasons, stories and philosophies and shocked by the underground idol world and sex clubs.

I have visited Japan many times in different seasons for different reasons in different moods in different states of mind but I have never been not smitten by it – by its urban magic and wooded wonder; its temples and shrines and skyscrapers and eateries; silent crowds in brightly-lit metros and raucous laughter in dim clubs; hostesses dressed in fantasy costumes handing out restaurant fliers and geishas in traditional garb waiting to board a Shinkansen. I have looked at the neon-lit night of the Ginza district and star-filled sky in Hakone with equal fervor, walked along the Sumida and the Kamo with identical sense of calm motion and observed social etiquettes and bowed and smiled and looked away and stood on the right side of the escalators in Tokyo and the right side in Osaka with equal incomprehension. I have reflected upon the utter impossibility of understanding the subterranean motivations and compulsions of a culture and yet admiring its outward depictions; I have been entranced with the aesthetic which with one flower or a spray of grass, a brushstroke or hand movement seeks to convey seasons, stories and philosophies and shocked by the underground idol world and sex clubs.

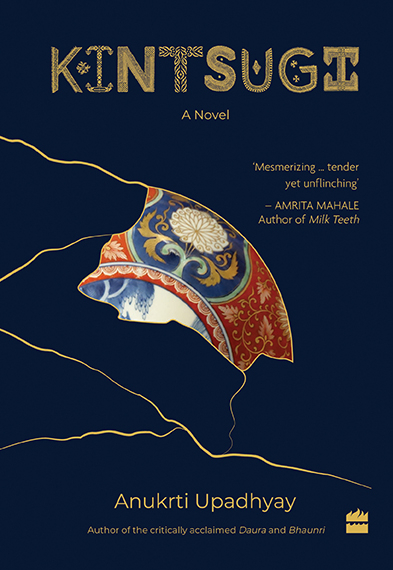

In short, the myriad contradictions of Japan, expressed in numerous ways, captivate and intrigue me, so much so that parts of my novel, Kintsugi, published by HarperCollins India, is set in Japan among Japanese characters. To me, Japanese literature illuminates these contradictions and isolations, universally experienced yet uniquely expressed.

I received Japanese literature, quite literally, as a gift. A dear and respected friend gifted us a copy of Musashi by Yoshikawa Eiji. A tome running into almost a thousand pages, it described the life and times of the legendary swordsman and ronin, Miyamoto Musashi. The story took place in the seventeenth century and traced Musashi’s life from a rowdy youth to master of swordsmanship and an enlightened person. It was a conventional adventure story, full of twists and turns, thrilling sword-fights and skin-of-teeth escapes, jealousy and romantic confusions. To me however, the Musashi was a glimpse of the old, strife-torn and feudal Japan, one that has disappeared leaving behind beautiful reminders like the Chiyoda castle which is now a part of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo and Matsuo Basho’s ethereal Haikus and one which I later explored again and again in The Tales of Genji and The Pillow Book.

What remained with me from this novel written in early twentieth century, was not the heroic, pragmatic, staunch Musashi, who ran away as often as he fought, but the myriad pictures of Japan – travellers kitted out in straw sandals and hats, white dust rising from winding roads, temples and tea houses, pine forests and mountains, pleasure quarters and wise geishas. And Otsu, a young woman raised in a village who pursued Musashi up and down Edo period Japan. I wondered at her – rejected and abandoned by Musashi and yet confident that they belonged together. The image of the coy, fragile, unseen-by-sun beauties of old Japan clashed with this determined woman walking down wild roads after the man she loved. The list of contradictions grew.

I began seeking out the works of Japanese authors actively. Browsing through an old book store somewhere in Mid-levels in Hong Kong, I came across a paperback copy of Tanizaki Junichiro’s turn-of-an-era epic, The Makioka Sisters. Set in the Showa period during the World War II years, it is a stunning tale of four sisters belonging to an affluent Osaka family – the conventional Tsuruko, vivacious Sachiko, demure Yukiko and rebellious Taeko - and how they negotiate their lives. The elegance and slow charm of life in the prosperous suburbs of Tokyo at a time when the world was caught in the toils of the cruellest war mankind had known, fascinated me. Again, it was the details of that life – the conventions of dress and make up, daily routines and social visits, shopping in the great stores of Tokyo, catching fireflies, viewing cherry blossoms that captivated me. In awe of his genius, I read every book of Tanizaki Sensei that I could find – Some Prefer Nettles, Diary of a Mad Old Man, A Cat, a Man and Two Women, Quicksand, Arrowroot, The Secret History of the House of Musashi. I reveled in the sensory splendour he invoked in his descriptions of elaborate, brocaded kimonos, rituals of watching a bunraku performance, food cooked on days of feast, gardens in autumn and summer. But it was when I read his long stories – The Bridge of Dreams, The Tattoist, The Story of Shunkin, The Terror, The Thief, Aguri – that I truly appreciated his great gift of crafting psychological, open-ended narratives filled with dark forebodings. He possessed an unparalleled skill in chracterisation and in story-telling against the living, breathing backdrop of a Japanese society in transition. He spelt his creed of aesthetic in his astonishing treatise, In Praise of Shadows – ‘Were it not for shadows, there would be no beauty.’

After Tanizaki Sensei’s works, I read more of the modern masters –Soseki Natsume, Akutagawa Ryunosuke, Mishima Yukio, Shusaku Endo, Kawabata Yasunari, Kenzeburo Oe. Their rich and diverse styles, intensity of portrayals of tradition and modernity had me in their thrall. The meticulous perfection of their writings, the layered and complex, and at times, shocking themes, their experiments in craft – all so subtle and so refined, that I found myself reading and re-reading them, discovering fresh aspects with every read.

Around this time my husband bought me a collection of short stories from the airport book shop at Narita Airport – Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman. It was by an author I hadn’t heard of –Murakami Haruki. This was before Murakami became the world-renowned author he is today and his works recognized as depictions of contemporary Japan. His stories came as a revelation to me. They were like a thunderclap of brilliance that destroyed all prejudices of plots and resolutions, setups and paybacks. Traversing between the real and the surreal, the quotidian and the fantastical, telling stories of the Japan I saw during my trips and the hidden undercurrents that I couldn’t, and exploring intricate themes of isolation and intimacy, they opened a new vista which was as much external as internal - a woman gives up sleeping, a green monster falls in love with a housewife, a monkey steals the name of a young woman, a man revisits his old sweetheart and another suffers inexplicable bouts of nausea. The characters and the stories revolutionized the way I had looked upon and read fiction. I read his works – The Windup Bird Chronicle, Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, A Wild Sheep Chase, Dance, Dance, Dance, After the Quake, Kafka on the Shore, Norwegian Wood - with mounting excitement. His complicated and fantastical plots, all with elements of mystery, repeated motifs of missing cats, people going on journeys, experiencing epiphanies at the bottom of wells, time-travels and dry, wry humour, made reading his works an adventure with elements of predictability. A contradiction again. One can never get too far away from contradictions in Japan and Japanese fiction and therein lies their allure for me - the opportunity to experience something and its opposite in one complete seamless experience.

I continue to read Japanese literature, eagerly and with great curiosity. I am amazed and inspired by the range, variety and experimentation with themes in contemporary Japanese authors. Whether it is Ogawa Yoko’s bewildering and intriguing collection of interconnected stories Revenge; Minato Kanae’s deeply disturbing Confessions; Kawakami Mieko’s slowly unfolding and sharply troubling Breasts and Eggs; Motoya Yukio’s disruptive and beguiling Picnic in the Storm, Morimi Tomihiko’s fascinating and fantastical Night is Short, Walk on Girl; Miyashita Natsu’s charming and gently paced Forest of Wool and Steel; Kawakami Hiromi’s subtle and surreal The Ten Loves of Mr. Nishino or any of the many, many more, they break boundaries of story-telling and are completely different from each other. Yet there is a common sensibility running through their differences, a subtle, veiled spirit that haunts them and which I seek for in book after book, another contradiction adding to the appeal of Japan and her literature for me.

小説『KINTSUGI』の書影

(Consultant, Wildlife Conservation Trust and Published Author (HarperCollins) )