An Evening of Noh and Kyogen 2021

(Free online video streaming)※Distribution closed on Saturday, December 24, 2022 at 2:00 p.m..

Every year in autumn, the Japan Foundation Kyoto Office organizes an event called “An Evening of Noh and Kyogen” to give people an opportunity to experience traditional Japanese culture, inviting international students, the Japan Foundation Fellows, and those enrolled at the Japanese-Language Institute, Kansai to join us. This year, however, the outbreak of COVID-19 has resulted in travel restrictions, making it difficult for students and Japanese Studies scholars abroad to come to Japan. To minimize the risk of virus transmission, we will take a new approach to this year’s event. Performances will be filmed without an audience and released for online video streaming, which will be made available to the public free of charge for one year.

| Date and time |

Friday, December 24, 2021, from 2:00 p.m. *Free for one year |

|---|---|

| Program | <Kyogen> The Snail Featuring: SHIGEYAMA Sengoro <Noh> Kiyotsune Featuring: KONGO Hisanori (Both productions will be presented with English subtitles giving a synopsis of the plot.) |

| Presented by | The Japan Foundation Kyoto Office |

| In cooperation with | The Kongo Noh Theatre Foundation Shigeyama Kyogen Troupe Art Research Center, Ritsumeikan University |

| Contact: | The Japan Foundation Kyoto Office Tel: 075-762-1136 |

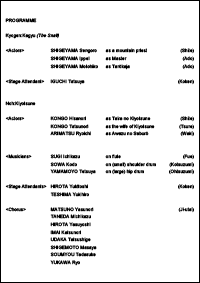

Programme Synopsis

Kyogen: The Snail

Synopsis

A mountain priest is heading home to Mount Haguro in Dewa after finishing his ascetic training on the sacred training grounds of Mounts Omine and Kazuraki. However, feeling sleepy halfway through his trip, he steps inside a bamboo thicket beside the road to take a little nap. In a different scene, there is a man whose grandfather has reached a venerable age and who wants him to live even longer. He hears that snail is an elixir of longevity, so he sends off his servant Tarokaja to catch one. However, Tarokaja has never seen a snail before and has no idea of what one looks like. “A snail is a creature with a black head, a shell on its back, and tentacles that sometimes protrude from its head. Some are as big as humans,” describes his master. Tarokaja sets out to the bamboo thicket just outside the village to find a snail, where he stumbles upon the sleeping mountain priest. Seeing his tokin (black hat worn on the forehead) and conch, Tarokaja mistakes him for the snail he is seeking and tries to bring him home.

<Kyogen>

Kyogen is a form of comic theater that emerged during Japan’s Muromachi period (around 1336 to 1573) and developed alongside Noh. It traces its origins to “Sarugaku,” a form of Japanese entertainment dating back to the late Heian period (mid-12th century). Later, the term “Nohgaku” was created to encompass these twin arts of Noh and Kyogen. While Noh is a tragic musical play, Kyogen is a comedy based on spoken dialog and wordplay. Performed as an interlude between acts of the more solemn Noh play, Kyogen creates comic relief, inducing laughter from the audience like a circus clown.

Stories of blunders in everyday life or making fun of the little quarrels among couples are the favorite motifs of Kyogen, a laughter theme unchanging even in modern days. Kyogen is a universal form of art that has made people laugh for centuries and will for centuries to come.

Noh: Kiyotsune

Synopsis

Awazu no Saburo, a retainer to the warrior general Taira no Kiyotsune, returns to Kyoto, carrying a lock of Kiyotsune’s hair, left behind as a keepsake. Suffering defeat after defeat in a series of battles and tormented by a sense of desperation at the fate of the Heike clan, Kiyotsune cast himself into the water, off the shore of Yanagi-ga-ura, Buzen Province (present-day Oita Prefecture). Informed of his passing, Kiyotsune’s wife resents her husband’s death, saying that she would have thought it inevitable if he had died in battle or of illness. “Since my pain grows even more unbearable whenever I see the hair, I will return it to its owner, who is now enshrined near the deity of Usa Hachimangu in Tsukushi.” She recites this poem and returns her husband’s memento to the shrine. When she hopes to see him at least in her dreams, his spirit appears to her. She blames her husband for throwing away his own life, and he reproaches his wife for spurning the lock of hair he had left behind. The loving couple who are tragically kept apart reunite this way, feeling full of reproach. To dispel his wife’s resentment, Kiyotsune narrates what happened up to the time he chose to die. He tells of how the Heike clan was exiled to wander in a remote region, lamenting that even the deity of Usa had turned aside from them. Interweaving his beautiful imagery with the actual scenery, Kiyotsune recounts how his clan set forth in their small boats, now cast adrift like floating autumn leaves. He tells of how his heart trembled when he saw a flock of egrets, mistaking the birds for the white flags of the Genji. With the moon shining down on his boat, he played his flute and leapt overboard. The story of his demise is rich in poetic beauty, creating a sense of transience. Kiyotsune reenacts his suffering in the realm of Warrior Hell, where he was condemned to fight endless battles. However, he has found salvation, saved by the merit earned from invocation of the Buddha’s name in his dying moment.

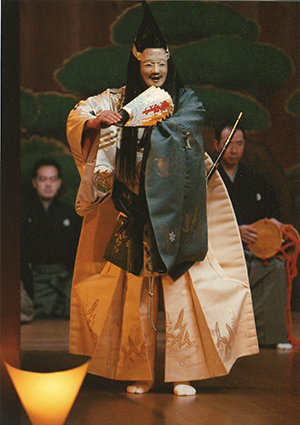

<Noh>

Noh is a form of theater that emerged during the Muromachi period (1336-1573), brought to its perfection by the father-and-son team of Kanami and Zeami, and since performed countless times to this day. It is a mask drama, but not all performers are masked. Masks are worn only by the main character (shite) and the attendant (tsure). When the main character is not masked, the face is kept completely expressionless, as if wearing a mask. Unlike other forms of theater, Noh does not use scenery or intricate props. Simple props (tsukurimono) sometimes used in Noh plays are intended to be more symbolic than realistic. Noh integrates elements such as masks and simple props in a dance-based performance, inviting viewers to unleash their imaginations and immerse themselves in the world created onstage. In Noh, dialogue is sparse. Rather, Noh sequences highlight the narrative of the main character, incorporating elements of poetry. Since Noh traces its origins to religious rites, many Noh sequences feature a deity in the lead role. This category of Noh is termed “god plays” (kami-noh or waki-noh). Noh plays can be divided into five categories: god plays, warrior plays (shura-noh), women plays (kazura-noh), miscellaneous plays (zatsu-noh), and demon plays (oni-noh or kiri-noh). Of the five categories, the warrior plays center on a warrior who, after a lifetime of battle, is condemned to wander in Warrior Hell, a world of eternal struggle within Buddhist philosophy. The women plays feature a female protagonist from the literature of the Imperial Court, embodying Zeami’s concept of yugen, an aesthetic term suggesting quiet elegance and subtle beauty.

Profile

SHIGEYAMA Sengoro

Born in 1972. Eldest son of Shigeyama Sensaku V. Birth name Masakuni.

First appeared on stage at the age of four as the protagonist of “Iroha.” Subsequently led such projects as the Hanagata Kyogen Kai, the Kyogen Shogekijo, “TOPPA!,” and the Kokoromi no Kai in his efforts to win new fans not just for Kyogen but also for Noh theater itself. Currently, he is working to communicate the appeal of Kyogen to a wider age-range of audiences by leading such projects as the Shigeyama Kyogen Kai, the “Cutting Edge KYOGEN” group (a revamped Hanagata Kyogen Kai), the Kashizuki no Kai in partnership with his younger brother, Shigeru, and the Waraenai Kai in partnership with Rakugo specialist Katsura Yonekichi. He has also actively collaborated with artists in other theatrical genres, including Yan Qinggu of the Shanghai Jingju Theatre Company and the Sichuan opera face changing master Jiang Peng. Succeeded to Shigeyama Sengoro XIV in 2016. Recipient of the Agency for Cultural Affairs’ New Artist Award of the National Arts Festival in 2005, recipient of Kyoto Prefectural Culture Award’s Distinguished Service Prize in 2008.

KONGO Hisanori

Born in Kyoto in 1951 as the eldest son of Kongo Iwao, the 25th-generation head of the lineage, Hisanori trained under his father from an early age. In September 1998, he became the 26th-generation head of the Kongo school of Noh, and in May 2005 oversaw the completion of the relocation of the Kongo Noh Theatre to the west side of Kyoto Imperial Palace. He has been designated by the Japanese government as a Holder of Important Intangible Cultural Property (collective recognition).

Along with “Mai-Kongo” (Dance Kongo), an ornate and dynamic style of acting unique to the Kongo school, he also specializes in the graceful and elegant style known as “Kyo-Kongo” (Kyoto-style Kongo) and is the only head of any of the five shite-kata schools of Noh to be based in the Kansai area. Beginning with his turn as director of the troupe that staged the Kongo school’s inaugural overseas performances in Canada and the United States, he has a wealth of overseas performing experience in countries such as Italy, France, Spain, Portugal, and Russia.

A recipient of the Kyoto Municipal New Artist Award and the Kyoto Prefectural Culture Award’s New Artist Prize and Distinguished Service Prize, he has also been honored with a Cultural Merit Award by the city of Kyoto. He is the recipient of the 67th Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology’s Art Encouragement Prize and in 2018 was awarded the Medal with Purple Ribbon, which is conferred by the Government of Japan to individuals who have contributed to academic and artistic developments.

As well as serving as President of the Kongo Nohgakudo Foundation, President of the Kongo Nohgaku-kai, and managing director of the Nihon Nohgaku-kai, he is also a visiting professor at the Kyoto City University of Arts and the author of Kongo-ke no men [Masks of the Kongo Lineage] and Kongo soke no noh-men to noh-shozoku [Noh Masks and Noh Costumes of the Kongo Lineage].

[Contact Us]

The Japan Foundation Kyoto Office

(3rd Floor, Kyoto International Community House 2-1 Torii-cho, Awataguchi, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto)

Tel: +81-(0)75-762-1136

- About Us Top

- About the Japan Foundation

- Donations

- News & Topics

- News & Topics Top

- Main Activities

- Main Activities Top

- Fiscal Year 2025-2026

- Fiscal Year 2024-2025

- Fiscal Year 2023-2024

- Fiscal Year 2022-2023

- Fiscal Year 2021-2022

- Fiscal Year 2020-2021

- Fiscal Year 2019-2020

- Fiscal Year 2018-2019

- Fiscal Year 2017-2018

- Fiscal Year 2016-2017

- Fiscal Year 2015-2016

- Fiscal Year 2014-2015

- Fiscal Year 2013-2014

- Events / Projects

- Press Release

- Press Release Top

- Fiscal Year 2025-2026

- Fiscal Year 2024-2025

- Fiscal Year 2023-2024

- Fiscal Year 2022-2023

- Fiscal Year 2021-2022

- Fiscal Year 2020-2021

- Fiscal Year 2019-2020

- Fiscal Year 2018-2019

- Fiscal Year 2017-2018

- Fiscal Year 2016-2017

- Fiscal Year 2015-2016

- Fiscal Year 2014-2015

- Fiscal Year 2013-2014

- Links