Wide-ranging Support–Japanese Language Education in South America

The Japan Foundation, Sao Paulo

KUNO Gen, NAKAJIMA Eriko, SATOMI Aya, KAKIUCHI Ryota

Three Japanese-Language Specialists and one Japanese-Language Senior Specialist are dispatched to The Japan Foundation, Sao Paulo (hereinafter “FJSP”). The following is a report of our work and the results thereof for fiscal 2019.

Support for the “Marugoto” Course – KAKIUCHI Ryota, In Charge of the Japanese-Language Course

The Cultural Alliance Brazil-Japan, a language educational institution in São Paulo, began offering courses in 2015 using “Marugoto: Japanese Language and Culture” (hereinafter “Marugoto”) as the primary teaching materials. Since 2014, we have prepared for the start of the course by holding a Japanese-language teacher training program once every six month before the new semester, mainly for handling new levels. The FJSP Japanese-language course team has been in charge of supporting and implementing the teacher training. Finally, in 2019, we started the Intermediate course, the highest level for Marugoto.

When we held the training for the start of Intermediate course, a certain change in awareness took place among the teachers who would be in charge of it. Specifically, rather than only sharing information and coming up with class ideas together once per semester, they decided to do it continuously throughout the semester. While the training for the start of the Intermediate course may have been the trigger for the idea, it was the teachers themselves who decided to make the change. Accordingly, the way we provide our support changed. We participate as observers in the regular meetings for the teachers in charge of the Intermediate course.

With change comes challenges and anxiety. And the same is true when trying to sustain the change. I hope to continue providing support to mitigate that challenge and anxiety as much as possible.

Results of Our Support for “Languages Without Borders” – SATOMI Aya

In Charge of Higher Education

Since 2016, FJSP has provided continuous support for Japanese-language courses in a project called “Languages Without Borders” (Idiomas sem Fronteiras in Portuguese) run by the Brazilian Ministry of Education for higher educational institutions. The main objective of this support is (1) to cultivate more people friendly to Japan through an interest in Japan fostered by familiarity with the language and culture, and (2) to train Student Tutors (Japanese-language instructors) majoring in the Japanese language at federal and state universities to run the Japanese-language courses. As of the end of 2019, a total of 156 courses have been held for 2,535 students (of which 1,538 completed the course), while 44 students gained experience as student tutors. In our survey in May 2020, we found that 29 out of the 44 students who tutored (approximately 66%) are now involved in Japanese-language education. I believe we can say that in addition to the effort by teacher coordinators of the Japanese-language courses at each university, the support of the FJSP has also been of help in training high quality Japanese-language teachers.

The “Language Without Borders project” is now entering a new phase and we are working with each stakeholder to arrange the program content. Moving forward, I intend to continue providing support that aligns with the conditions and needs of higher educational institutions.

Tutors teaching Japanese-language during a “Languages Without Borders” class.

Opinions on the Act on Promotion of Japanese-Language Education from South America–NAKAJIMA Eriko

In charge of South America

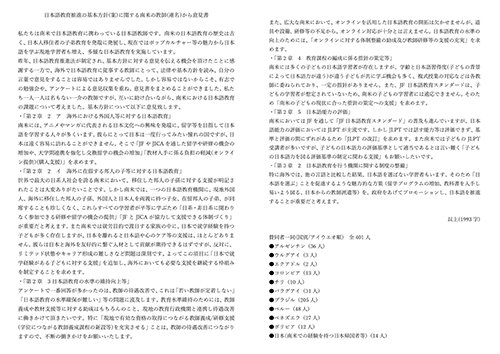

Japanese-language teachers associated with the Japanese communities in various countries in South America collected and submitted comments on the basic policy of the Act on Promotion of Japanese Language Education, promulgated and entered into force on June 28, 2019, and submitted them with signatures from 401 individuals in the 10 South American countries as a public comment.

The reason this came about was that the proposal for the law called for a framework for “Japanese language education for the Japanese children resident overseas”, to which those involved in heritage language education throughout the world raised their voices calling for further clarification. Unlike the state of heritage language education in other area countries, many of the learners in South America who would fall under the definition of “Japanese children resident overseas” are 3rd or 4th generation Japanese immigrants, but there are also many 1st and 2nd generation children as well as children who have studied in Japan, and research shows that many of those commute to Japanese language schools run by the local Japanese community. In addition to Japanese language schools, those Japanese communities have also expanded into running primary and lower secondary privately established schools with public nature at which a diversity of students study together, including Japanese immigrants, non-Japanese, Japanese citizens, and returnees from Japan. This situation raises a variety of issues which may seem unique to South America at first, but the same problems may also be relevant to the next 50 to 100 years of heritage language education.

Incidentally, while there does not currently exist a single teachers association representing all of South America, the teachers involved in collecting the aforementioned opinions have since formed their own group. The aim of the group is to build a network covering all of South America to communicate about the future of Japanese-language education on the continent from a local perspective. I will consider how to support them in a way that emphasizes local cooperation.

The public comments from South America on the Basic Policy on Promotion of Japanese Language Education (Draft)

Teachers Learning From Each Other–KUNO Gen, Japanese-Language Chief Advisor for South America and Brazil

Of the educational institutions in Brazil with a Japanese-language education program, roughly 60% are institutions run by the Japanese community outside of schools. I visit 12-13 communities each year to give lectures for teacher training workshops hosted by the teachers associations of the Japanese community. Many of the teachers who teach the Japanese language at these institutions have never studied Japanese-language education themselves. For that reason, many are worried whether their teaching methods are correct, and wish to learn better methods from Japanese-Language Specialists.

But when I ask them how they teach, it is often the case that their methodologies are extremely appropriate for their situations. For that reason, I make an effort in the training program to point out to the teachers that the methodologies they have arrived at through trial and error are in alignment with theory of second language acquisition and other theories.

On the other hand, the methods of one teacher are often new to others. Accordingly, I also emphasize at the teacher training that the participants have much to learn from their fellow teachers who are highly experienced in the classroom. This gives me the feeling that the role of the Japanese-Language Specialist is to help the teachers learn from each other rather than to teach them directly.

- What We Do Top

- Arts and Cultural Exchange [Culture]

- Japanese-Language Education Overseas [Language]

- Japanese-Language Education Overseas [Language] Top

- Learn Japanese-language

- Teach Japanese-language

- Take Japanese-Language Test

- Know about Japanese-language education abroad

- The Japanese-Language Institute, Urawa

- The Japanese-Language Institute, Kansai

- Japanese-Language Programs for Foreign Specified Skilled Worker Candidates

- Japanese Language Education for Japanese Children Resident Overseas and for the Descendants of Migrants

- Archives

- Japanese Studies and Global Partnerships [Dialogue]

- JF digital collection

- Other Programs / Programs to Commemorate Exchange Year

- Awards and Prizes

- Publications