Kusama Yayoi, Shō-chan

Heisei period, Heisei period, 2013

(c)YAYOI KUSAMA. Courtesy of Ota Fine Arts

Tokyo/Singapore/Shanghai

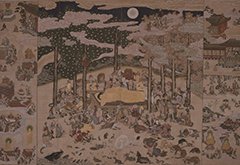

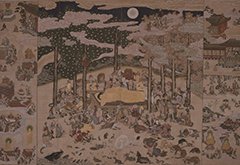

Ozawa Kagaku, Festival Dancing

Edo period, 19th century

HOSOMI MUSEUM

Haniwa Dog

Kofun period,

6th–7th Century

Miho Museum

(c)Kenji Yamazaki

The Japan Foundation is collaborating with the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art to present The Life of Animals in Japanese Art at these two American art museums.

Throughout history, people in Japan have lived in coexistence with animals and nature. For over 1,500 years, since the era of ancient burial mounds known as the Kofun period, animals have appeared in various forms as important motifs for visual art and literature, where they are seen as human companions and sometimes have supernatural powers that make them superior to humanity. One of the characteristic aspects of Japanese culture is the significance of the role played by animals in art. This exhibition examines a wide range of animal-themed art closely related to the lifestyles, spiritual climate, and religious views of Japan through a diversity of media, including painting, sculpture, lacquer art, ceramic art, metalwork, cloisonné enamel, woodblock prints, textiles, and photography.

The show incorporates over 300 precious works from about 100 major collections in Japan and the United States. Of those, close to 170 works, including seven Important Cultural Properties, are from Japanese collections, most of which have never been shown outside Japan.

This historic opportunity has been made possible thanks to the cooperation of many experts and specialists in both countries. The exhibition is curated by Robert Singer, curator and head of the Japanese Art Department at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Masatomo Kawai, director of Chiba City Museum of Art, who are working with a team of Japanese experts participating as joint curators. A former Japan Foundation research fellow in fiscal 1973, Mr. Singer lived in Japan for a long period of time at the beginning of his career studying Japanese art.

This is the fourth major exhibition of Japanese art to be held at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.—following Japan: The Shaping of Daimyo Culture 1185-1868 in 1988, Edo: Art in Japan 1615-1868 in 1998, and Colorful Realm: Japanese Bird-and-Flower Paintings by Ito Jakuchu (1716–1800) in 2012. Interest in Japanese art is on the rise, with the Ito Jakuchu exhibition attracting 231,658 visitors over one month. By taking a new approach with a focus on animals, The Life of Animals in Japanese Art is expected to contribute to a deeper understanding of Japanese culture in the United States.

| Venue 1: |

National Gallery of Art, Washington

June 2–August 18, 2019

Exhibition title: The Life of Animals in Japanese Art

Number of visitors: 86,674

Exhibition view

|

| Venue 2: |

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

September 22–December 8, 2019

Exhibition title: Every Living Thing: Animals in Japanese Art |

| Organizers: |

The Japan Foundation

The National Gallery of Art, Washington

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art |

| With Special Cooperation from: |

The Tokyo National Museum |

| With Cooperation from: |

The Chiba City Museum of Art

The Suntory Museum of Art |

| Supported by: |

All Nippon Airways |

| Curators: |

- Robert T. Singer, curator and department head, Japanese art, LACMA

- Masatomo Kawai, director, Chiba City Museum of Art

|

| Co-Curators: |

- Masaaki Arakawa, professor, Gakushuin University

- Ryusuke Asami, supervisor, curatorial planning dept., Tokyo National Museum

- Hiroshi Ikeda, honorary researcher, Toyko National Museum

- Hiroyuki Kano, former professor, Doshisha University

- Mika Kuraya, chief curator, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

- Nobuhiko Maruyama, professor, Musashi University

- Tomoko Matsuo, senior curator, Chiba City Museum of Art

- Yasuyuki Sasaki, curator, Suntory Museum of Art

|

| Japanese Executive Committee: |

- Hiroyasu Ando, president, Japan Foundation

- Masatomo Kawai, director, Chiba City Museum of Art

- Shingo Torii, director, Suntory Museum of Art

- Masami Zeniya, director, Tokyo National Museum

|

About the exhibition

Consisting of eight theme-based sections, the exhibition displays wonderfully expressive art with animal motifs from as long ago as the 5th and 6th centuries all the way up to modern times, including depictions of animals by contemporary artists. Featuring mythical creatures as well as real animals not native to Japan, such as lions and elephants, which Japan learned about from China and far away India through trade and the introduction of Buddhism, the exhibition covers a broad range, spanning national borders, eras, genres, and media.

We sincerely hope that a large audience will enjoy getting to know the animals that have been companions of the Japanese people since ancient times, and leave the exhibition with an increased interest in the culture that underlies this art.

Exhibition structure and key exhibits

This show consists of the following eight sections. (Section titles are working titles.)

Introduction

Haniwa Waterfowl

Kofun period, c. 5th century

Tokyo National Museum

Haniwa were made and placed on burial mounds during the Kofun period. Depicting a variety of things, including people and animals as well as houses and shields, they are thought to have been used in combination to reenact stories or ceremonies.

Haniwa depicting animals, together with those depicting people, were made in abundance in the 6th century, and were generally shaped in the form of chickens, waterfowl, falcons, cormorants, and other birds, as well as dogs, wild boars, cattle, deer, and horses. Although fewer in number, haniwa depicting fish, monkeys, and flying squirrels have also been found.

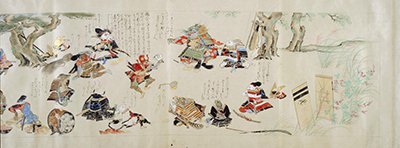

Twelve Zodiac Animals

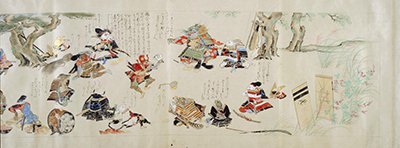

Twelve Zodiac Animals at War

Edo period, 1840

Tokyo National Museum

The twelve signs of the Chinese zodiac are calendar terms that originated in ancient China. They were also used to represent the twelve-hour clock, points on the compass, and the twelve-year cycle Jupiter makes in the heavens as seen from earth. Ancient astronomers divided the course Jupiter takes through the sky into twelve sections, assigning one of the characters of the Chinese zodiac to each. This enabled people to determine which year it was based on Jupiter’s position. The system would eventually be adopted by Japan. At some point—some speculate that it was during the Han Dynasty—the characters representing each of the years in the twelve-year zodiac cycle became associated with ordinary animals, resulting in the current system in which each symbolizes an animal—rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, rooster, dog, and boar.

Religion: Buddhism, Zen, Shinto

Pair of Guardian Lions

Heian period, 10th century

Collection of Lynda and Stewart Resnick

One of the most familiar animal statues in Japan is the komainu, a stone-carved guardian dog found at the gates of Shinto shrines. Although the origins of this statue can be traced back to distant locations in Western Asia and India, the shape and name of komainu statues in Japan stem from Japan’s adoption of a variant that was merged with a mythical Chinese animal. Although these statues are typically placed so that they are oriented towards each other but facing straight ahead towards the approach to the shrine, these particular komainu are thought to have been placed at an angle.

Shaka Passing into Nirvana

Edo period, 1727

Seiraiji, Aichi Prefecture

When Buddhism came to Japan, it brought with it images of animals from India and China that did not exist in Japan, such as lions, elephants, and water buffalo. The arrival of mythical creatures from China, such as the Chinese dragon and phoenix, however, preceded the introduction of Buddhism. These creatures were, therefore, already well established in Japanese society, and can often be seen featured in designs on plates and clothing. One of the most frequent depictions of animals was in the nehanzu images of the supine Buddha entering nirvana. In these scenes portraying the passing of Buddha being mourned by a variety of living beings, animals are shown situated beneath Buddha’s disciples and believers. Some images even include creatures such as crabs, frogs, and centipedes.

Kōen, Monju Bosatsu Seated on a Lion, with Standing Attendants

Kamakura period, 1273

Tokyo National Museum

The origins of this grouping of Manjushri (Monju Bodhisattva) seated on a lion with four standing attendants emerged from the belief in the sacred Mount Wutai in China, considered the earthly abode of Manjushri. Waves are shown below the rock the lion stands on because Japanese worshippers believed Manjushri crossed the seas from Mount Wutai to come to Japan.

Many images of Manjushri seated on a lion are shown as part of the Shakyamuni trinity in Buddhism, in which Manjushri together with fellow bodhisattva Samantabhadra, seated on an elephant, flank Gautama Buddha.

Myth and folklore

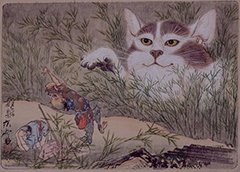

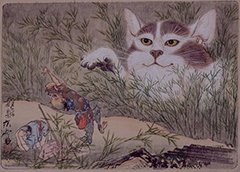

Kawanabe Kyōsai, Monster Cat from Seisei Kyōsai Picture Album

Edo–Meiji periods, before 1870

Private collection

Animals are sometimes incorporated into amusing stories in order to personify or caricaturize someone or something as a metaphor or to convey a moral. The artist Kawanabe Kyosai(1831-1889) was proud of his skill at depicting animals, and although little is known about the story behind this painting, the depiction of the cat is unforgettably intense.

Phoenix

Muromachi period, 14th century

Rokuonji

The phoenix is a mythical bird from Chinese folklore that is said to appear when a wise man rules the realm. This phoenix adorned the top of the roof of the Golden Pavilion in Kyoto, which was built by the shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu in 1398. It was removed during repairs to the Golden Pavilion during the Meiji period and left in storage, and, therefore, escaped the fire that burned down the pavilion in 1950. Originally, it would have been a shiny gold color, like the Golden Pavilion itself.

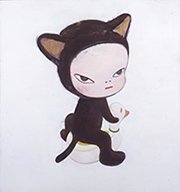

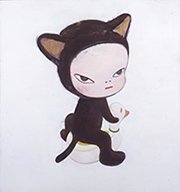

Nara Yoshitomo, Harmless Kitty

Heisei period, 1994

National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

Yoshitomo Nara is known for producing paintings depicting children who seem to glare at the viewer. This child appears to be something between a human and an animal, giving the impression that Nara is fascinated by the close relationship between the two.

Uchikake with Phoenix and Birds

Meiji period, 19th century

Kyoto National Museum

This yuzen-dyed uchikake outer robe depicting a large number of birds (momodorizu) was made as the wedding gown for the daughter of a wealthy Osaka merchant. Centered prominently on the back is a phoenix with wings spread out wide, surrounded by 99 birds, including a peacock, dove, pheasant, parrot, chicken, and quail. Inside the robe is a sunrise and a red-crowned crane.

The World of the Samurai

Suit of Armor with Dark Blue and Red Lacing

Edo period, 18th century

Okazaki City Museum

Among the armor and weapons expressing the aesthetic sense of samurai warriors, many masterpieces were produced that incorporated animal designs.

This suit of armor belonged to Honda Tadataka (1698-1709), who became head of the Murakami Domain in Echigo Province (modern-day Niigata Prefecture) at the age of seven. Tadataka’s ancestor, Honda Tadakatsu (1548-1610), was a general who served Tokugawa Ieyasu, and whose helmet with deer antlers was very famous. Some Edo period feudal lords marked their rise to the head of their clan by emulating the shape or characteristics of their ancestor’s armor in their own armor. This suit of armor is an example of such a practice.

Owari School, Sword Guard with Crab

Muromachi period, 16th century

Tokyo National Museum

From around the 16th century, samurai wore their long and short swords through the left side of the belt of their hakama trousers with the blade facing up, and it was right around this time that sword guards of various designs began to be made. This particular sword guard has a bold composition depicting nothing but a crab with large raised claws in the middle of a circle, and with the background completely cut out. The meticulous and refined technology used for making sword guards and other metal fittings for swords became the basis for modern craftsmanship in the Meiji period onwards.

Helmet Shaped like a Turbo Shell and Half Mask

Edo period, 17th century

Tokyo National Museum

Demand for suits of armor increased dramatically at the end of the 16th century, when infantry lines armed with spears and firearms were central to the art of war. Producing an iconoclastic helmet design became the subject of competition, and various forms became fashionable. These were referred to as tosei kabuto (“modern helmets”) or kawari kabuto (“distinctive helmets”). Helmets that were actually used in battle were of simple design and made of materials that would break on impact with the branch of a tree, but once the era of long, stable peace was established in the middle of the 17th century, very unusual helmets boasting great craftsmanship came to be made in large numbers. This headpiece, modelled after a turban shell, channels the hardness of the shell and its horns.

The Study of Nature

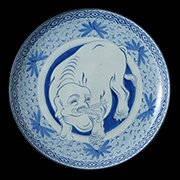

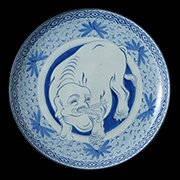

Charger with Elephant

Edo period, 19th century

Segawa Takeo

The study of animals through observation and realistic representation became a popular pastime in the 18th and 19th centuries.

A large Imari ware plate from the late Edo period, well over 30 centimeters wide. Such plates had previously been considered no more than ordinary tableware in general use, but they are now being reevaluated. Expanding the potential of simple ransai pottery through the use of cobalt pigment during the time of the middle to late Edo period when the government often issued decrees prohibiting extravagance in order to promote frugality, the plates demonstrate a pure form of the edogonomi aesthetic, which prioritized the removal of unnecessary distractions from the main focus or subject. This plate depicting a giant white elephant would probably have served as the centerpiece of a festive banquet.

The Nature World: On Land, in the Air, and in Rivers and Seas

ManabuMiyazaki, Black Bear Plays with Camera

Heisei period, 2006

Izu Photo Museum

Human interest in animals that live in a broad range of environments is growing. How has our view of animals changed?

Since the 1970s, Miyazaki Manabu has been photographing animals using an automatic camera set up outdoors that operates 24 hours a day. In front of the mechanical eye of a camera, free from feelings of caution, animals display a nobility that they never would show when face to face with people. However, this image of a bear acting like a cameraman also reveals something very human.

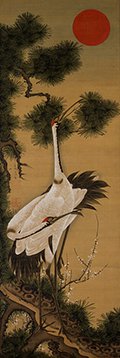

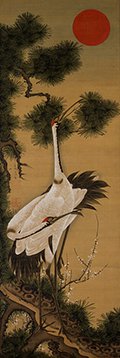

Itō Jakuchū, Pair of Cranes and Morning Sun

Edo period, c. 1755–1756

Tekisuiken Memorial Foundation of Culture

Many pictures of flowers and birds carry a meaning of good omen, and are typically exhibited at festive occasions. The rising sun depicted in this picture represents a New Year’s Day sunrise, with both the crane and the evergreen pine tree symbolizing long life.

The World of Leisure

Kyōgen Monkey Mask

Edo period, 17th–18th century

Tokyo National Museum

This section presents designs featuring humorous animal depictions used to parody authority and representations of charming animals that were used in the performing arts.

The life of a Kyogen actor is said to start by portraying a monkey and end by portraying a fox, and actors often do play a monkey in Utsubo-zaru (“The Monkey's Quiver”) when appearing on stage for the first time. Child actors are a good choice for this because Utsubo-zaru deals with a feudal lord whose heart is moved by the innocence of a monkey who performs tricks. Other plays, such as Saru Muko (“Monkey Son-in-law”), have many monkey parts, so numerous monkey masks remain.

Catalogue

Editors: Robert T. Singer, Masatomo Kawai

Published by Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford

First published in May 2019

Total pages: 323 pages

Languages: English

Book size: 9 x 12 in.

ISBN: 978-0-691-19116-4 (hardcover)/978-0-89468-413-5 (softcover)

Price: $65.00 (hardcover)/$39.95(softcover)

[Contact Us]

The Japan Foundation

Visual Arts Section, Arts and Culture Dept.

Person in charge: Okabe, Suzuki, Sueyoshi, Matsumoto

Tel: +81-(0)3-5369-6061 / Fax: +81-(0)3-5369-6038