Event Report “In a Voice Playful, In a Voice Introspective: A Conversation with Norman Erikson Pasaribu and Paolo Tiausas”

For profile of the panelists, please click here.

Postcolonial Language and History

Fujii: While I may not be a polyglot—I speak only Japanese and English—my study of American literature has given me a front-row view of the incredible diversity of contemporary English writing. Working with immigrant literature, I’ve often found myself translating voices from all over the world, and along the way, I have realized something fascinating: Native speakers of English aren’t the only ones who claim the language as their own. Writers across the globe, even in non-English-speaking regions like Gaza, are crafting literature in English, connecting with the language in unique ways to share their stories. It’s a phenomenon that is both exciting and complex—and for me, nothing short of eye-opening. Today, I’m eager to dive into this topic with Paolo Tiausas and Norman Erikson Pasaribu, exploring their own relationships with the English language.

Southeast Asia is a vast and varied region, and while that description may include a lot under a broad umbrella, it has shaped my work in meaningful ways. Over the past five years, I’ve had the opportunity to translate books by Southeast Asian authors writing in English. Among these works are Malay Sketches by Alfian Sa'at, a remarkable Singaporean poet, playwright, and novelist; and Insurrecto by the acclaimed Filipino writer Gina Apostol. Through these works, I’ve come to appreciate the richness and depth of Singaporean and Filipino literature. This journey has only just begun, and I look forward to further exploring and translating the voices of Asian writers who craft their stories in English.

Before I go on, I’d like to share a personal reflection related to my family history. My grandfather was an officer in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II and served in various parts of Asia. He rarely spoke of his experiences, so the details remain a mystery, but I know he spent time in China and Indonesia. That may be why, even two generations later, I have an intense curiosity about the war in Asia. Looking back, I realize that many of the novels I’ve translated concern war, and I wonder if I am drawn to such stories partly because of echoes from past generations. With that in mind, I’m especially eager to hear my guests’ thoughts and experiences today.

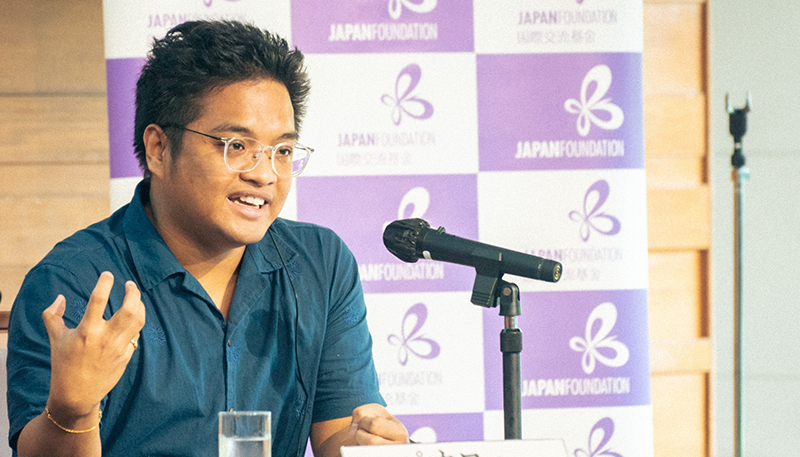

Paolo: I’m Paolo Tiausas, a poet and performer from Pasig City, Metro Manila—home to the Pasig River, one of the longest and most iconic rivers in the Philippines. For the past fifteen years, my poetry has been deeply rooted in contemporary Filipino society, which is vibrant and complex yet often challenging to fully understand. My fascination with youth culture led me to explore issues of gender, with a focus on masculinity. Like many countries, the Philippines has a strongly patriarchal society, and men hold a privileged position in the social hierarchy. Attending an all-boys high school, I witnessed that personally—both the unspoken rules and the harsh realities. Even as a young teenager, I saw how the principles and practices of patriarchy left a lasting impression. That’s why the question of Filipino identity is at the heart of everything I create. It’s a conversation I won’t—actually can’t—ignore.

I typically communicate and write in Filipino, with nearly all my published poetry composed in my native language. However this year, I have begun to translate my poems into English. The Philippines boasts over eighty languages, each with its own distinct characteristics, making conversations with people from different regions a bit tricky at times. As a result, English has become the common language Filipinos often turn to. Chances are, most Filipinos that you know can speak English quite well.

Filipino is rich in Spanish loanwords, which have blossomed into unique expressions over time. Today, the Filipino culture and language is a colorful tapestry woven from many influences. Filipino mingles with English, Spanish, Chinese, and regional languages, creating a vibrant linguistic landscape that inspires my poetry. While other writers may prefer pure Filipino or stick exclusively to English, I want to embrace the fluidity of language, writing in the everyday speech that surrounds me. I also recognize the privilege of my position as a straight male writer and strive to approach my work with a critical eye. In my first poetry collection, I explored themes of masculinity and male identity. The original title, Lahat ng Nag-aangas ay Inaagnas, is a play on the words angas (swagger) and agnas (rot), implying that swagger leads ultimately to decay. I translated the title into English as All Men Ending. This collection garnered nominations for both the Philippine National Book Awards and the Madrigal-Gonzalez Best First Book Award.

My second poetry collection is titled Tuwing Nag-iisa sa Mapa ng Buntong-hininga (When Lonely in the Map of Sighs). I’m proud to say that this collection was honored as Best Book of Poetry in Filipino at the 40th National Book Awards. To kick things off, I’d like to read a poem from my first collection, All Men Ending. This piece is called “Superhero(PDF: 93KB)”. The word for men in Filipino is lalake, and you’ll notice that it’s woven into the fabric of the poem.

Norman: I’m Norman Erikson Pasaribu, a Toba Batak poet and writer from Indonesia. I’ve published two poetry collections and also written short stories, which have been translated into English. One of those is Happy Stories, Mostly, translated by Tiffany Tsao and released by Tilted Axis Press in the UK. To my surprise, this book was longlisted for the 2022 International Booker Prize, giving my work a wonderful platform on the global stage.

My creative pursuits are closely tied to my identity—particularly my queerness. As a gay person from the Toba Batak tribe, my personal journey is deeply connected to Indonesia's postcolonial landscape. Indonesia was ruled by the Netherlands and other European nations, and was even colonized by Japan. I was thrilled that Prof. Fujii touched on the history of war, because it's vital for those of us in Southeast Asia to openly discuss our colonial past and share our stories in our own voices.

Today, I’d like to begin by reading a poem from my collection Sergius Mencari Bacchus (Sergius Seeks Bacchus). The piece is titled “Ia dan Pohon”—which can be translated as “He and the Tree”, “They and the Tree”, or “She and the Tree”. Since Indonesian third-person pronouns are gender neutral, I’ve taken the liberty of translating the title as “He and the Tree”. In Batak mythology, which predates colonial influences, trees and forests are regarded as our elder brothers. Everything is created from a single essence, and trees existed before us. Unfortunately, the rampant deforestation in modern Sumatra, largely driven by wealthy elites and conglomerates, has had devastating effects on nature. Many Batak people are Christians, and since Jesus was a carpenter, I felt compelled, as a member of the Batak community, to offer my apologies to the trees at the beginning of this poetry collection. I carry the burden of having betrayed the forests as a younger brother.

Exploring the Deep Ties Between Masculinity and Violence

Fujii: I’d love to explore in more depth the poetry of both of you. Let’s start with Paolo. I read your own English translation from Filipino of the collection All Men Ending. The final poem, “Superhero”, powerfully explores masculinity—a theme that runs throughout the book. What stood out most to me was the poem’s closing words, “intended. Otherwise.”. What a striking way to end. The word “intended” appears similarly in the collection’s opening poem, “All Men Ending”, which closes with the words “new intention”. This makes “Superhero” appear to be a deliberate bookend, tying the collection together. What inspired you to write this poem?

Paolo: As you pointed out, the word “intended” appears in both the opening and closing poems of the collection—very much by design. I mentioned earlier that I went to an all-boys school—and I will swing back to that in a moment. However, let’s first rewind to 2016, when the Philippine presidential election sent the country into turmoil. You probably know of former President Duterte. Under his rule, extrajudicial killings surged—sometimes escalating into outright massacres. That’s where the imagery in my poetry comes from. Duterte’s so-called war on drugs led to shocking violence, with countless people killed by the police. Many were accused of drug use, but investigations later revealed that some had no connection to drugs at all. Even children as young as four or five years old were targeted, forced to wear cardboard signs around their necks that read “Don’t be like me”. One case that shook the nation was the murder of seventeen-year-old Kian delos Santos, who was killed by police on his way home. He pleaded, “Please don’t shoot me; I have school tomorrow”, but they killed him anyway. All of this was fueled by a leader who built his image on hypermasculinity. Duterte wasn’t known only for his brutal policies—in fact, his persona was wholly machismo. He spoke crudely, cursed openly, and addressed the media as if he were in a bar with his bros. He had no filter, no remorse—saying things like “This person should die” or “We should kill them”.

Watching it all unfold, I was hit with a strange sense of déjà vu. This kind of masculinity, this culture of violence—I’d seen it before. It had played out on a smaller scale in my own school life. The former president’s treatment of his people was eerily similar to how boys in my high school interacted. Crude jokes, constant competition to prove dominance, and casual cruelty masked as humor—it was all there. From offhand verbal jabs to outright bullying, the atmosphere was charged with a subtle but relentless aggression. I couldn’t shake the question: If we had managed to stop this behavior in the classroom, would my country have taken a different path? That question became the heart of this poetry collection. And the more I reflected, the more I realized I wasn’t just a witness—I was part of the problem too.

Men often say, “I didn’t mean it that way”. I remember a moment in high school when we were lined up in the hallway, and a classmate made a wolf-whistle as a female teacher passed by. There was an uproar, and the teacher demanded to know who was responsible, but no one admitted to it. Even though the behavior bordered on harassment, I’m sure that the guilty classmate would have simply claimed, “I didn’t mean it like that”. Countless incidents are brushed off with that same excuse. This is why the theme of intentionality versus unintentionality in men's behavior became the foundation of my poetry collection. That realization inspired the line “the history of men is a history of mistakes, intended or otherwise”.

Fujii: Your words resonate with me because I had similar experiences in my Japanese high school. Having grown up in that kind of environment myself made your words really hit home. Your poems start with specific events that quickly coalesce into a broader concept, encouraging us to reflect on civilization itself.

Challenging the Concept of Conformity

Fujii: Next, Norman, I would like to explore your poem “He and the Tree”, which you so kindly shared with us. You pointed out the fascinating fact that the Indonesian language makes no gender distinctions in third-person pronouns. Meanwhile, a gender is assigned in the English title, “He and the Tree”. How do you feel about that shift in perspective?

I was also struck by the imagery in the lines “too close to the foundation” and “from afar they would check on each other”. It seems like distance is a prominent theme here, so what’s your take on that? And what about the idea of “God, who had three branches—like a tree”? There’s definitely something deeper there.

Norman: The title of my poetry collection Sergius Seeks Bacchus includes the names of two Catholic saints, and you may wonder why I chose them. In conservative Indonesia, people often see someone like me, a queer individual, as a sign of the apocalypse, but even we queer folks occasionally want to be viewed as someone sacred too [laughs]. Like my queer friends, I want to be a saint, not a sign of the apocalypse, and I tried to create a world reflecting that in my book. James Baldwin once said that you can’t move forward without shedding self-loathing, and I experienced a transformation similar to that while writing this collection. While Christianity teaches that God is a Trinity, I intentionally wrote in this poem that God is “like a tree”, because after Christianity took root among the Batak people, precolonial beliefs and cultures became increasingly difficult to access.

Now, I have a fascinating anecdote to share. At a time when many countries were being colonized, European powers swept through Indonesia, snatching up Batak treasures for auctions and museums. In contrast to this, the Japanese military left behind a treasure trove of weapons. Traveling through Indonesia, I often hear tales of hidden Japanese arms or even sightings of samurai in the mountains [laughs]. It’s an intriguing irony—one group takes everything, while the other leaves remnants behind—which symbolizes the queer reality of the postcolonial era in Indonesia. In my book, I frequently write about God, but I wouldn’t call myself particularly devout; I believe it’s okay to treat divinity with a lighthearted touch. Honestly, many of my queer friends aspire to become spiritual leaders, and in my own life, I also sometimes feel the urge to speak authoritatively. On the cover of my book is a figure with its face erased, which was designed by a friend as a powerful message: Refuse to be excluded from anything.

Fujii: So, the simple setting of a person and a tree actually has deeper significance related to one’s place in society. It definitely makes me want to reread your book and reflect more on its significance.

Norman will now treat us to another poem, “A Flyer” (“Brosur”).

Norman: My poem “A Flyer” is about a program that is designed to bring happiness to everyone. As an Indonesian, I often wonder if true happiness is within reach. Many of us feel immense pressure to meet our neighbors' expectations, and it is tough to be our true selves in such a community-oriented society. For instance, if I get sick, my colleagues and neighbors might raise money to help me get to the hospital, which is kind but also can be viewed as nosiness. For queer individuals, life takes a turn after the age of twenty-five, and the questions about why they aren’t married start pouring in—even though they may have two husbands [laughs]. So, in Indonesia, it’s essential to wear many different masks, even among friends.

Fujii: This poem is written in a very mechanical style, as if the program itself is speaking or the flyer’s descriptions are being relayed on their own, making us question whether “you” really exist. It touches on human tastes and preferences in love, using exactly those two words—“tastes” and “preferences”—in the English translation, like data that is analyzed. I’m curious about your choice of style here. I also noticed that the original Indonesian included several familiar English loanwords, like program (program), analisis (analysis), and koekstensif (coextensive). What were your main intentions in writing this poem?

Norman: This poem definitely has a mechanical vibe, primarily due to its app-like format, but there's more to it than that. I wrote it as a young queer poet fueled by a desire for revenge against heterosexual writers—essentially as a rebellion against traditional notions of poetry. I wanted to disrupt those norms and evoke a sense of irreverence. While the poem contains Christian imagery, it does not come from deep devotion; it’s precisely because I’m not overly religious that I chose those expressions. At its core is the desire to push back against the community. The term “program” is casually used by people in Jakarta, and I didn’t intend it to sound foreign; I wanted to irritate those who use it. The more they use it, the more they might come to dislike it and question whether following the app's guidelines can actually lead to happiness. In this poem, I also wanted to tackle the idea of “conformity”. As queers, we’re always fighting this battle, grappling with whether to come out, share ourselves on social media, or stay offline. These everyday struggles often distract us from crucial discussions about queer rights. I feel that queer individuals are expected to be good people—generous and kind. But shouldn’t everyone be allowed to be a little annoying sometimes? We can all be bothersome—I’ve been called annoying plenty of times [laughs]. Ultimately, this poem conveys that everyone, regardless of their sexuality, deserves the chance to be happy. We all have the right to fulfillment and respect in life, without qualifiers or conditions related to sexuality.

Can Filipinos Board the Ark?

Fujii: Next, let's hear Paolo read his poem “Territory” (“Teritoryo”) (PDF: 63KB). This piece is rich in biblical references, including Noah’s ark and the New Testament, creating a vivid tapestry of imagery. I’m particularly intrigued by the perspective of the speaker, who refers to themself as “I”. In the poem, the speaker acknowledges the many nameless victims of violence and engages “you” with poignant questions, which itself raises an interesting question: Where does the “I” truly stand within this narrative?

Paolo: This poem is actually fresh off the press—I wrote it just a few weeks ago! During my month at the Kyoto Writers Residency, I was blessed with a fantastic writing environment and was also able to explore many of Kyoto's most famous spots. I soaked up the sights, enjoyed the food, and had an incredible time. This project was my first experience away from my home country for an extended period.

I had traveled abroad for work before, but this residency gave me the freedom to use my time for reflection. Interestingly, I felt more Filipino than ever, and this experience abroad highlighted my status as an outsider. During the opening ceremony of the Kyoto Writers Residency, I was asked to talk about writing through “alien materials”. I responded that I don’t see myself as using alien materials; rather, I consider myself an alien Filipino. This ties in with Norman’s insights and reveals an intriguing aspect of postcolonialism. The Philippines has a unique culture shaped by four hundred years of Spanish colonization, followed by forty years of American occupation and a brief period of Japanese control. These influences often clash and obscure one another, resulting in a distinctly peculiar Filipino identity. In Kyoto, I truly felt like an outsider, yet that experience inspired me to write something authentically Filipino. I want to create poetry that directly reflects my identity. While my earlier works include Filipino realities, sharing those experiences outside the Philippines has been challenging, and I wanted to explore that directly in this poem.

My personal connection to floods also informs my writing. You may have heard about the massive typhoon that recently hit the Philippines, causing severe damage in the Bicol Region. Many areas were submerged, leaving people stranded on rooftops, desperately seeking help. Sadly, this is all too common in the Philippines, where large-scale floods occur frequently. In fact, I almost drowned in a flood in 2009.

Now I can look back on it and laugh. At that time, I was trying to get home, but the water had risen to my waist. I thought, “It's been raining for six or seven hours—I can't go home. I should head to the mall instead”. I spotted an elevated bridge leading to the mall and figured I could manage the short flooded path from the station. But I didn’t realize there was a massive canal, seven or eight feet deep, right in my path. Unable to see the canal through the floodwater, I was walking with my earbuds in, feeling pretty cool—until I sank straight into the canal! I remember struggling to swim but didn’t know how. After flailing about and sinking again, someone nearby grabbed my hand and pulled me out. In that moment, all the curses I knew came to mind as I shouted, “What just happened?!” It was a major wake-up call. Even now, floods continue to plague the Philippines. My identity as a Filipino and those flood experiences fueled my writing of this new piece.

The Philippines is deeply influenced by Christianity, which is our predominant religion, and we know all the stories in the Bible. This got me thinking about our challenges as a postcolonial nation, and I often ask myself if we truly belong here. If a flood like the one in Noah's time were to strike today, would Filipinos even be allowed to board the ark? What if we had to sneak aboard like stowaways? This surreal idea sparked my desire to write, capturing the sense of being crammed into corners or boxes where we don't belong. In my work, the ark symbolizes this struggle—"they” discover “us” and attempt to erase our presence. The violent imagery in the poem reflects experiences familiar to every Filipino. For example, I mention being “packed into boxes and sent home by plane”—a stark reminder of the many Filipinos who work abroad as domestic helpers and the stories of their bodies being returned in boxes when they die overseas—or sometimes not returned at all. So, this poem takes the perspective of stowaways, expressing that while “we” have been discovered, I for one, am still angry. “We” don’t want to negotiate; instead, we want to ask someone these questions: What do you intend to do with us? Are you planning to make us suffer even more?

Norman: Let me share a quick thought on the water theme. I am often asked why my poetry features so much rain and flooding. My answer is this: That's just life. Plus, like Paolo, I can’t swim [laughs]. In Indonesia, it’s common for gay folks to meet at pools, but water cannot always be viewed as a source of life; it can also represent death or fate. Floods can wash away everything you own, and I carry some terrifying memories of those brown waters. I grew up in Bekasi, a satellite city of Jakarta, where floods were a regular occurrence. During the pandemic, they got even worse, making us feel like we were being punished, but really, it was caused by gentrification of the area.

Embracing Play

Fujii: Both “Territory” and “A Flyer” perfectly reflect this event’s theme of playfulness, while exploring the shared theme of finding a place in society. I believe that this reflects a desire to challenge dominant values and ways of thinking in order to carve out one's own place in the world.

Now, Norman will share another piece, “My Dream Job (PDF: 173KB)”, which is also a new creation.

Norman: This poem serves as the title piece of my second collection, with the title being a play on words: the name of the biblical prophet Job from the Old Testament and the word “job”, meaning employment. I began writing it in Indonesian, put it on hold for a while, and then picked it up again around 2022 to finish. I used to work as an accountant at the Indonesian tax office, a demanding job with a high salary. Unfortunately, after winning an award, I lost that position, and after that, I started writing the poems in this collection.

The biblical prophet Job never cursed God, even after losing everything. But because of what happened to me, I found myself cursing as often as three times a day [laughs]. In that respect, I'm like an anti-Job, an antiprophet. There’s a myth of piety in the Christian community, which I observed particularly in my mother and her friends, and that inspired me to write this book.

Fujii: Your frequent use of water imagery comes through clearly in this piece, along with the number three, as in the three branches of the deity in “He and the Tree”. Here, “three” emerges again, whether through combinations of three or in the concept of the Holy Trinity. While you incorporate religious motifs, you create a unique linguistic polyamory, which sets your work apart. This piece truly reflects your distinctive style of generating something fresh.

I’d like to ask a bit more about translation. Norman, you mentioned that you initially wrote in Indonesian and then shifted to English for your new project. Does writing in English feel like you're translating your own work? Also, Paolo, you translated your own poems into English, which became the collection outlive poems. When translating Filipino poems into English, what were the challenges you encountered and changes you made?

Norman: When Keiko Nishino, the translator of “My Dream Job”, mentioned her desire to keep the double meaning of the word “Job”, I wholeheartedly agreed. I view myself as an experimental poet and want translators to have fun with the text too. Although my poems are each personal expressions, I don’t think of them as having a singular voice; they’re just one voice for others to elaborate on through their own understanding. One of my desires in writing this collection was to play with the language, and I hope all translators feel free to do the same.

Writing in English has a different feel than writing in Indonesian. I dream in Indonesian, and I explore my past experiences in that language, whereas writing in English is like having new adventures abroad. For example, during my first literary residency, I used the word “devout”, but my pronunciation was such that the audience heard “default”. It’s amazing how one word can shift the meaning entirely—often leading to misunderstanding.

Translation can often magnify misunderstandings, especially in poetry, and discussions about what gets lost in translation can be pretty animated. Yet, a powerful insight from a Vietnamese poet resonates with me: mistranslations, deviations from the original, and whatever is lost in translation—these elements are part of poetry too. That perspective really freed my approach to language. Occasionally, I find myself lost when writing in English, but I believe that as long as I keep playing with words, I can discover something meaningful.

For me, writing poetry is like an aerobic workout—an exhilarating, yet sometimes painfully fun, linguistic experience. In “My Dream Job”, I explore the concept of linguistic polyamory, but the whole collection also tackles the complexities of Dutch colonization in Sumatra. What at first appears to be a love story quickly reveals itself to be a thriller. The Batak churches had to demonstrate that Christianity wasn't a violent religion in order to promote their faith. Yet, rereading colonial documents showed me how drastically my youthful beliefs had changed. That's why I wanted to portray innocence in the beginning of the collection with the impression of a love story and polyamory. As readers dive deeper into the poems, however, they'll discover that violence is an undeniable part of the world we live in.

In my collection, there's a poem called “Tell Me Your Body Count”. While “body count” is slang for the number of romantic partners someone has had—a topic queer people frequently discuss—the term also has the grim meaning of “death toll” and was often heard during the colonial era. I read a letter written by a German prisoner in which he mentioned that ten soldiers and fifteen German priests had died but completely omitted any record of the number of Toba Batak casualties in the colonial wars. It’s striking that the violent meaning of “body count”, a term my friends and I use casually, has been largely forgotten in today’s society.

Paolo: Like Norman, I dream in my native language, and it deeply affects the way I think, although I’m constantly translating my thoughts into English. Even now, every thought I have is in Filipino. When I write poetry, I want to bring in playful elements, which is today’s theme. I know what typical Filipino poetry conveys and which topics are considered poetic, but my work doesn’t often fit that mold. Many prefer pure Filipino or beautiful themes, using familiar metaphors to express their feelings about the country. As Norman pointed out, English often creeps in because we use it in our daily conversations.

When I’m unsure how to translate a Filipino word into English or the other way around, I love to mix the two languages and playfully experiment. For example, in my poem “Superhero”, I wrote “edukado, doktorado”. Edukado means “educated”, while doktorado has a fun twist. In the Philippines, we joke about “doctoring” documents, referring to forgery, but the word also refers to someone with a doctoral degree, so in English it becomes someone with a doctorate who fights for humanity. This kind of wordplay is rarely found in formal Filipino poetry.

Let’s talk about the opening line of “Territory”. In English, it’s translated as “Bird unchained by sky, hurry your flight...” But in Filipino, it’s "Ibon mang may layang lumipad..."—a direct nod to a beloved 1929 national song, often sung at protests and gatherings. The song’s metaphor is clear: a caged bird crying for freedom, just like the Philippines itself. Now, back to your question. Translating something like this is tough. How do you recreate that same weight in English? When I say “Ibon mang may layang lumipad...”, every Filipino immediately knows the reference. But in English, there’s no good equivalent, so I decided to play with it.

A partial literal translation would be “a bird with the freedom to fly”, but that felt flat in a poem. So, I played around with the words and structure until I landed on “Bird unchained by sky”. It’s not a perfect match, but it captures the rhythm and wordplay of the original. Translation can be tough— I suffer a lot when the right words won’t come. But as Norman said, it’s also fun! It’s not just about converting text; it’s about reshaping it into something new.

Moving Forward from the Past

Fujii: You each bring your own unique style to writing and translation. Norman’s words “painfully fun” and Paolo’s words “suffer but fun” reflect a shared experience, and Paolo’s repeated emphasis on playfulness speaks volumes. It’s not just about creativity—it’s about self-reflection, being present, and confronting history. That blend of depth and playfulness ties your works together. Now, let’s hear from the audience.

Question: Norman, how do you balance your Toba Batak heritage with the broader Indonesian language in your writing? The poet Faisal Oddang has talked about navigating between his Sulawesi roots, and Makassarese and Indonesian languages. Do you face a similar challenge? And Paolo, how does mainstream Filipino society react to the reinvention of myths tied to Christian traditions?

Norman: Good question. Indonesian is, in a sense, a colonial language, enforced by the state especially after the 1965 mass killings as a means for people in Indonesia to navigate society. Mastering the language opened the doors to government jobs and opportunities across the country. Yet, Indonesia boasts a rich tapestry of traditional languages, including Toba Batak, and those of us identifying with such a tradition can sometimes feel stifled. I grew up speaking Indonesian, the language my parents gifted me. My relationship with Christianity is also complex, being rooted in my upbringing in a Christian household. I’ve explored Western gay culture extensively, which has been liberating for me. In this postcolonial context, embracing contradictions is key. We can’t change the past—colonization and war are irreversible. But the future still offers space for us. That's why I negotiate with the Indonesian language as a queer person here, aiming to create a space not just for myself but for others like me. Ultimately, I believe this will benefit Toba Batak communities and the working class as well. Through this negotiation, we can move forward together.

In 2018, I traveled to the Banggai Islands and met one of the last speakers of a minority language. When I asked him why he hadn’t taught it to his children and grandchildren, he said, “Because they wanted to work for the government”. This highlights a stark reality in Indonesia, where traditional languages are being erased. Writing in Toba Batak can be challenging. Books in that language are often so complex that I’ve never really delved into them. Last year, I received a scholarship to explore connections with the Batak community in Germany, but my visa application was almost denied. So, to reconnect with my own cultural roots, I first had to apply for a Schengen visa. This is the ironic reality we face today.

Paolo: When it comes to crafting new myths with religious imagery, I've noticed interesting reactions in Philippine society. I haven't shared much about this before, but when I self-published All Men Ending in 2020, the most touching part of the experience was the flood of messages from friends, especially women, expressing their gratitude for my writing. Their support truly boosted my confidence. However, when the book was nominated for and won an award, the judges completely overlooked its themes. Despite its clear exploration of masculinity, they didn’t mention that at all. One judge simply read my bio and said, “He has reasons to win this award”, offering praise without discussing the content. It was a strange experience to be recognized without any reference to the actual work. This leads to an important question: Are people really ready to hear these messages? Some are, but unfortunately, many aren’t, especially men. This realization only strengthens my resolve to spread the message and keep writing. It’s crucial to talk about these issues with other heterosexual men—why we’re struggling with this and how our unintentional actions can harm others. The conversation must continue. We should strive to be better feminists for women and queer folks, don’t you think?

Fujii: Colonial history and dominant values like heteronormativity and masculinity present real challenges. Norman, you captured it well when you talked about being annoying. I see how both of you embrace new language to boldly tackle these issues head on. Thank you both for today!

Photos: SATO Motoi

- What We Do Top

- Arts and Cultural Exchange [Culture]

- Japanese-Language Education Overseas [Language]

- Japanese-Language Education Overseas [Language] Top

- Learn Japanese-language

- Teach Japanese-language

- Take Japanese-Language Test

- Know about Japanese-language education abroad

- The Japanese-Language Institute, Urawa

- The Japanese-Language Institute, Kansai

- Japanese-Language Programs for Foreign Specified Skilled Worker Candidates

- Japanese Language Education for Japanese Children Resident Overseas and for the Descendants of Migrants

- Archives

- Japanese Studies and Global Partnerships [Dialogue]

- JF digital collection

- Other Programs / Programs to Commemorate Exchange Year

- Awards and Prizes

- Publications