Japanese-Language Education in Iran: Quantitative and Qualitative Changes

University of Tehran

SUDO Nobuhiro

During 2019, a year which marks the 90th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Japan and Iran, Japanese-language education continued to develop here in Iran.

Firstly, the number of Japanese-language educational institutions and learners increased. At the University of Tehran, there is a Department of Japanese Language and Literature and master’s degree program specializing in Japanese-language education within the Faculty of Foreign Languages and Literatures, and at the Foreign Language Center on a separate campus, a public Japanese language course for members of the general public has been held. In the past, the public Japanese language course attracted approximately 80 participants each year, but now the course has more than 100 students, who have been divided up into a wide variety of about 20 classes, depending on their language abilities. Also, from 2019 the University of Tehran has introduced a new Japanese conversation course and Japanese culture course for students other than Japanese-language majors, and approximately 20 new students have taken up these courses.

Outside Tehran, since 2017 Al-Mustafa International University in Qom has also been offering Japanese classes as an optional course. At the University of Tabriz in Tabriz in northwestern Iran, Japanese classes as a second foreign language have been available since 2018, and at the Ferdowsi University of Mashhad in the eastern city of Mashhad, preparations are underway to launch a Japanese-language class. When I was first dispatched to Iran in 2017, the only university offering Japanese-language education was the University of Tehran, but this number has now grown to at least three institutions. I will continue to provide support so that Japanese-language education continues at these institutions where it has just begun.

The number of people taking the Japanese-Language Proficiency Test (hereinafter “JLPT”) is also increasing. In 2015 there were just 53 test takers, but this number has continued to increase to 85 in 2016, 97 in 2017, and 152 in 2018. When you think that the number of test takers fluctuated between 50 to 65 people in the years up to 2015, it would appear that in recent years enthusiasm for Japanese-language learning has increased, and more people are aware of the existence of the JLPT.

The number of attendances in the Iran Japanese Speech Contest is also increasing. There were 13 attendances in 2015, 7 in 2016, 10 in 2017, 16 in 2018, and 15 in 2019, meaning that for the past few years there have always been more than 10 attendances. You can also see that the contest is attracting attention from the fact that about 150 people come to watch and listen each year. These are the quantitative results of ongoing Japanese-language education in Iran to date.

Event introducing Japanese culture. The shape of a heart is entwined in the Japanese character for “love.”

Qualitative Changes

Some readers may be thinking, “Rather than increasing the number of contestants in the Japanese speech contest, surely it is more important to ensure quality?” In terms of their content, we have heard speeches that argue for the importance of pure literature in one’s life, or speeches that give an insight into the inner workings of someone’s mind, such as the changes the mind experiences when learning kanji (Chinese characters). There have also been speeches in which the speechmaker talks with passion about something that they have studied, including everything from the Achaemenid Empire to Toyota’s corporate practices and policies. There have also been participants who have spoken about their childhood experiences of living in Japan. Although I have only been involved in the contest for two years and therefore can’t compare the content with speeches given five, or ten years ago, we have received positive opinions from Iranian audience members and embassy staff about the quality of the speech contest improving, which makes me believe that some modest improvements have been seen. My feeling is that the contestants generally tend to want to deal with lofty themes.

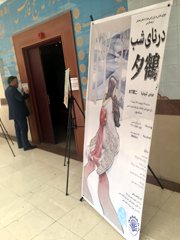

Poster for the play Twilight Crane,

displayed in a hall at the University of Tehran.

This preference for loftiness can also be seen in foreign-language plays. For several years the University of Tehran has been holding a foreign-language drama festival, for which I and other teachers help the students with preparations. In 2017, the students performed Chichi Kaeru (Father Returns) and in 2018, Yuuzuru (Twilight Crane). In 2019, the plan is to perform Yoroboshi. Many students find value in “actually performing a Japanese play that also has literary value,” so they select the play that they want to perform independently, taking time to plan their performance, and memorize long lines. They also devise their own stage directions, and create their own costumes and props. When I see the students paying attention to such details with a level of enthusiasm that you don’t normally see, it really makes me realize the importance of learning something independently. From the preparatory stages through to the actual performance, all the performers and staff undergo a tremendous transformation in terms of their Japanese-language skills and personalities. Many people who come to watch the performance also say, “I would like to try. Next year I want to take part as a performer.” This could be something that is true not just for theatrical performances but for the performing arts in general (although I don’t really want to make it sound like I am an expert), but I feel that there are certainly things that it is impossible to quantify, such as the transformation and growth of people through rehearsals and emotions that can only be shared by being there in the theater together. The teachers providing guidance and instruction also found themselves experiencing a transformation, as they struggled with how to provide advice that would add to the performance and make it better.

At the beginning of this report I wrote that Japanese-language education has continued to develop, and there are in fact many people in Iran who have visited Japan and many more with an interest in all things Japanese. It is not unusual to encounter people with a deep knowledge and appreciation of Japanese language, literature and culture. Thanks to the efforts of those involved in Japanese-language education, the portion of the population who have an interest in Japan has started to become apparent in numeric terms, including the number of JLPT test takers and the number of spectators at the Japanese speech contest. I will continue my own efforts to ensure that these qualitative and quantitative developments continue stably into the future.

- What We Do Top

- Arts and Cultural Exchange [Culture]

- Japanese-Language Education Overseas [Language]

- Japanese-Language Education Overseas [Language] Top

- Learn Japanese-language

- Teach Japanese-language

- Take Japanese-Language Test

- Know about Japanese-language education abroad

- The Japanese-Language Institute, Urawa

- The Japanese-Language Institute, Kansai

- Japanese-Language Programs for Foreign Specified Skilled Worker Candidates

- Japanese Language Education for Japanese Children Resident Overseas and for the Descendants of Migrants

- Archives

- Japanese Studies and Global Partnerships [Dialogue]

- JF digital collection

- Other Programs / Programs to Commemorate Exchange Year

- Awards and Prizes

- Publications