Connecting Japanese-Language Teachers in the Immense Area of Sumatra

The Japan Foundation, Jakarta

(Central Java Province/Special Region of Yogyakarta Secondary Educational Institutions)

SUGISHIMA Natsuko

When many people hear Sumatra Island, they probably picture it as the place where there was an earthquake and tsunami, or as a small island, but in reality it is the sixth-largest island in the world, with a total area of 473,500km2, more than the total area of Japan’s entire territory. Across the 10 provinces on this expansive Sumatra Island, there are close to 93,000 Japanese-language learners studying the Japanese language (according to The Survey on Japanese-Language Education Abroad 2018 by The Japan Foundation). I am dispatched to the town of Padang, which is located more or less in the middle of Sumatra Island’s western coast, and my duties center on supporting Japanese-language teachers at secondary educational institutions in West Sumatra Province. In fiscal 2020, I widened the reach of my activities to Sumatra Island as a whole, not just West Sumatra, and have been implementing support for the Japanese-language teachers scattered about the region through in-person workshops and online training.

Workshops in Remote Locations

“Nihongo☆Kirakira,” the Japanese-language textbook for high school students that The Japan Foundation, Jakarta developed based on the new curriculum in 2017, is being increasingly used at high schools. However, simply changing the textbook and leaving the teaching method the same will not achieve the goals of the new curriculum, which are to build a learner-centered learning process and nurture 21st Century skills. Since the teachers of West Sumatra also take part in the usual Japanese teachers associations, it is possible to create regular learning opportunities for them, but since I was dispatched in 2018, I was concerning that the teachers in other regions of Sumatra Island might be having difficulties. In light of that, in fiscal 2020, I also visited Aceh Province, North Sumatra Province, Jambi Province and Riau Province, all areas I had been unable to visit to provide teacher support the previous year, and held workshops with the high school teachers in each region. At these workshops, the teachers and I thought about how to strengthen 21st Century skills with Japanese-language education.

Workshop in Aceh Province (What does society look like in the 21st Century?)

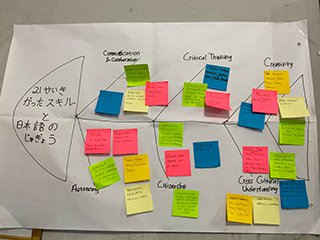

Workshop in North Sumatra Province (21st Century skills and Japanese-language education)

In regional workshops, in some cases after learning teaching methods, everyone comes up with a lesson plan together and then the next day the teachers take turns at taking a class with actual high school students. Observing the students’ reactions makes it possible to better clarify what has changed compared to the teaching methods used up to now. The teachers also engage in a very animated debate during the reflective discussion that takes place after the class. In addition, in many cases, I am the first foreigner the students in regional locations have ever met, and I get a great deal of energy from the students who approach me after class and suggest “Let’s take a photo together!” in their carefree way.

Providing Support Online

For teachers who to a certain extent have already learned about 21st Century skills, and who are highly motivated regarding Japanese-language learning, in addition to in-person teacher training, I also held an online course. It is an extremely high-level, seven-week course in which the teachers themselves study culture and the Japanese language as learners using “Hirogaru, get more of Japan and Japanese” (https://hirogaru-nihongo.jp/en/), a website developed by The Japan Foundation. Following that they try putting assignments that incorporate 21st Century skills into practice, reflect on what they have learned, and come up with lesson plans. The reflection process generated many realizations from the teachers who participated, including: “It occurred to me that teachers will also have to enhance their 21st Century skills,” “I thought I understood critical thinking1 and had been teaching it up to now, but it may well be that what I was making my students do was merely thinking,” “Neither I nor my students have nearly enough autonomous learning skills2 yet,” and “teaching Japanese culture and the Japanese language in combination may well increase students’ motivation for learning.” I feel that by sharing a seven-week period of learning with teachers living in distant regions who are not able to meet in the usual Japanese teachers associations, it is possible to create new connections between the teachers, which is a positive aspect unique to holding training online.

Regarding Future Support

Accompanying the impact of the spread of COVID-19 cases at the end of fiscal 2020, schools closed in Indonesia, and classes were shifted to an online format. Due to that, it is not possible to predict when face-to-face classes will reopen in schools or when in-person teacher training will be held, and this situation looks set to continue going forward. Amid that, I am catching glimpses of teachers making an all-out effort to maintain their educational activities, even while following a process of trial and error. This includes teachers who had not experienced online learning and teaching up to now having a go at participating in webinars, or sharing their experiences of trying to teach online with Japanese teachers association members. Among teachers who had participated in online training up to now, there are some who have been able to draw on those experiences of learning online as students to transition smoothly to online classes. Over the course of the fiscal 2020 year, I will do what I can with my limited ability to continue to provide remote support to those teachers, and to come up with new formats for teacher support.

1. Critical thinking: To consider things and information from a variety of angles and understand them logically and objectively, as opposed to simply accepting them blindly.

2. The skill and ability to learn independently and autonomously.

- What We Do Top

- Arts and Cultural Exchange [Culture]

- Japanese-Language Education Overseas [Language]

- Japanese-Language Education Overseas [Language] Top

- Learn Japanese-language

- Teach Japanese-language

- Take Japanese-Language Test

- Know about Japanese-language education abroad

- The Japanese-Language Institute, Urawa

- The Japanese-Language Institute, Kansai

- Japanese-Language Programs for Foreign Specified Skilled Worker Candidates

- Japanese Language Education for Japanese Children Resident Overseas and for the Descendants of Migrants

- Archives

- Japanese Studies and Global Partnerships [Dialogue]

- JF digital collection

- Other Programs / Programs to Commemorate Exchange Year

- Awards and Prizes

- Publications